Have you ever cried when a celebrity died? This is my third time. I cried when Prince, died in 2016. I cried when Cicely Tyson died in 2020. And I cried today, when I watched this clip of Sarah Harding singing her heart out and I realised that I had somehow, despite all reported evidence, convinced myself that she would still be here in 2022, that she would be included in the 20th anniversary celebrations of Girls Aloud and that we would have one last bittersweet memory of her time as part of something that had brought us so much joy over the years, to cherish before the end. The delusion is over.

It’s probably very uncool to admit how upset I have been about the death of someone I don’t know personally. The sadness speaks to what it represents, though: hundreds of beautiful, silly, fun memories that belong to me, and many more thousands that belong to other people. The sadness speaks to the understanding that not only will we not get to make more memories like that, even remembering the ones we already have will never feel the same again.

I put my phone down for a couple of hours to take a break from the overwhelm of the timeline and when I returned I happened to click on the Guardian’s official obituary when I was scrolling through the trending topic. I’m conscious that I might be feeling over sensitive, but to my mind the sketch of Sarah it presents is mean-spirited and reductive, omitting mention of her achievements as one-fifth of Girls Aloud, one of the UK’s most successful girlbands in favour of recalling trivial, tabloid details from her, at times, publicly messy private life.

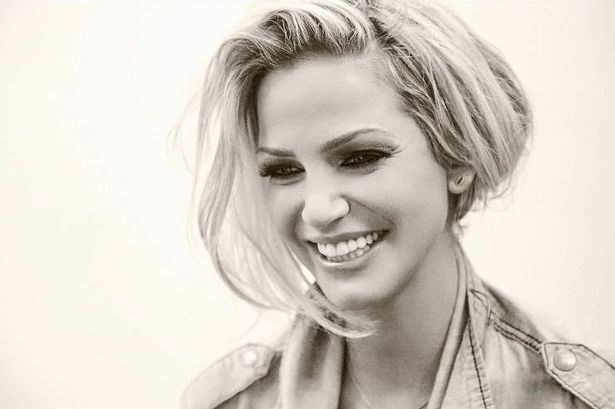

The obituary spends more time on the media persona of Sarah Harding than it does the human being at its centre. That human being was vibrant, unpredictable, girl-you-meet-in-the-club-toilets friendly, a kinetic force on stage and the second most reliable live vocal after Nadine – even taking into account that iconic bum note. She was known as Hardcore Harding for her relentless partying at the height of her fame, and because she was less predictable and more up for anything than her bandmates. You couldn’t help but notice a little instability, underneath it all. A little fracture in her heart. A fault line. It was part of her charm.

She had the same sort of quality in her character that simultaneously compelled and repulsed us towards Caroline Flack, to use the most recent example that springs to mind at this late hour. Obituaries like these are written and edited and published without a blink because as a society, we are uncomfortable with these women. Their fragility frightens us. We can’t stand how sincere their barely concealed vulnerability is, we resent it, in fact, because we ourselves spend so much time being disingenuous at work and selectively truthful at play, and because we almost have to do that for survival, or so we think. We package up their complexities and label them with a limited archetype, deliberately making them more tricky to sympathise with because – and this is the really clever part – these archetypes are designed to make us think that they are built around the woman, when the truth is they are being crammed into a box manufactured as standard and shuttled along the conveyor belt of fame. We are guilty of time and again of damaging these women in transit – dropping them, or squeezing them too tightly in our grasp. Either way, they break.

I would never normally presume to speak for an entire group of people, but I feel fairly confident that all Girls Aloud fans would agree with me when I say that we loved Sarah because of her vulnerability, not despite it. I have a distinct memory of describing her as “obviously transparent” on an old blog I kept around that time, when I was a clumsier writer. What I was trying to gesture at, was this notion that Sarah knew she wasn’t fooling anyone when she presented as “Hardcore” and maybe wasn’t really trying to. We knew that she alternately wore her bravado as a mask and wielded it as a shield and she knew that we knew. Wanted us to, I think. We loved her because we knew she was an absolute caner and because we knew she wasn’t just an absolute caner, in the way that her media caricature was painted. I did not know Sarah, but I knew girls who behaved like her. I’ve, at times, been girls who behaved her. Sometimes the hurt you hold in your heart is too hard to hide wholly convincingly. There is relief on all sides when everyone sticks to the script, plays along. None of us are skilled enough at improv for what happens if we break the fourth wall.

Many more informed words than mine have been written about divas, camp queens, gay icons and the idols of “hun” culture – why these women appeal, what that says about us, and (less often, more tentatively) how can we stop literally loving them to death. This is not that. I write not to explain or explore these concepts but to acknowledge that within their limitations, and as much as she could be made out from this distance – popstar to fan – Sarah was seen by so many. We understood what we could, from what she showed us.

All that to say that it is not that it is incorrect to present Sarah Harding, in death, “sins” first. Indeed, if there happens to be anywhere to go after life, I’m almost certain that’s how you arrive at the gates. Not incorrect, then, but unfair. She projected that image at us and we held up the Mirror to reflect it back at her. In her absence, we should be adding dimension, not flattening her further.